First published in National Indigenous Times on October 31, 2018.

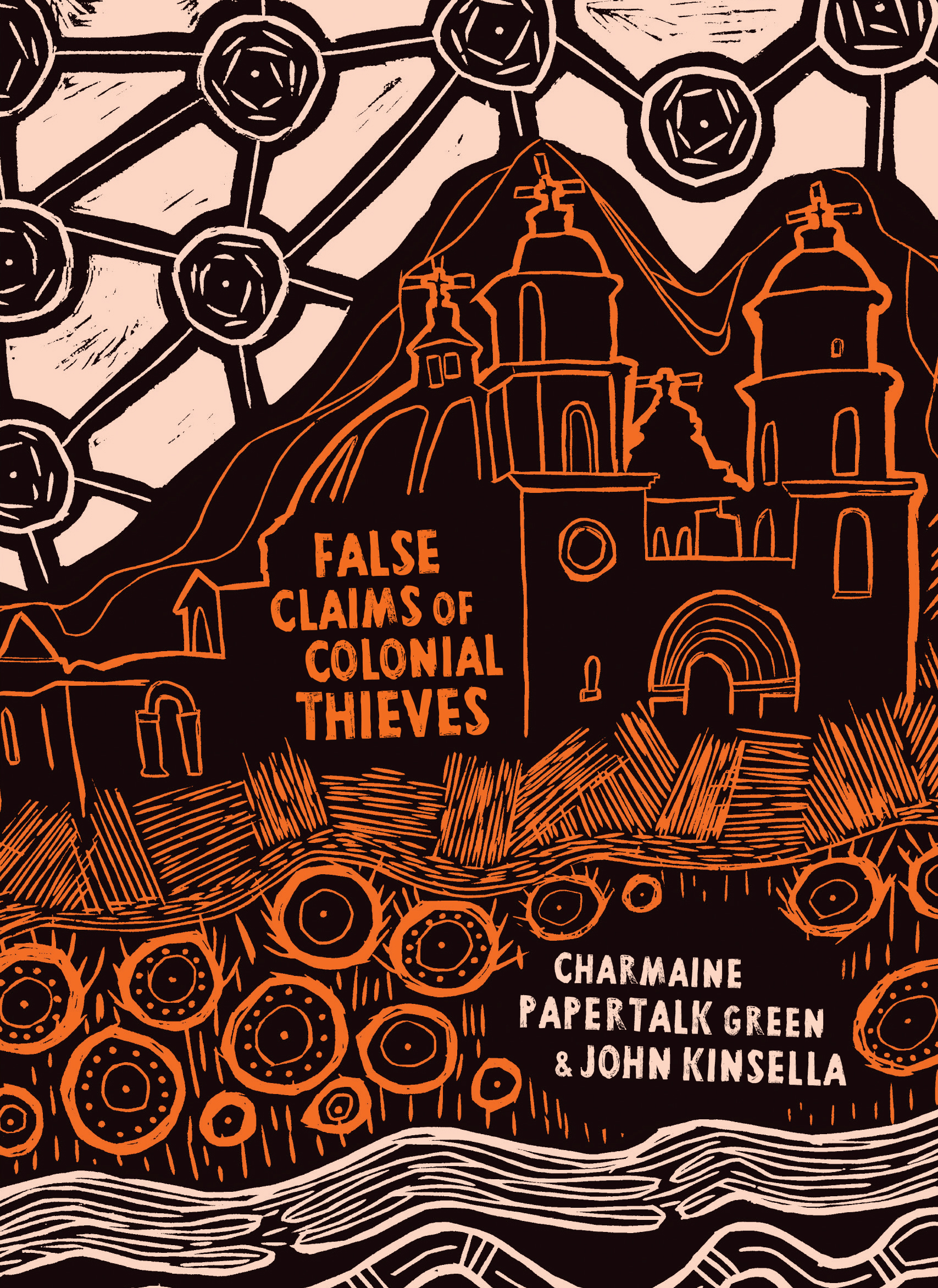

False Claims of Colonial Thieves starts with mining. Charmaine Papertalk Green reflects on her grandmother, glad that the only mining she knew was the mining of ochre for body and hair during ceremony. She reflects on the mountains that disappear and turn into cars; on the contemporary mechanical mine dream time animals.

This is Western Australia, depicted with great heart by the Yamaji poet and artist, who writes alongside celebrated WA poet John Kinsella. Kinsella and Green call to each other across cultures, seeking ‘a third space’ where black and white Australians can truth tell and share stories about our country and our history.

There’s light and shade: in one breath, Green shows us her ancestral lands singing with wildflowers, in another, we learn of the rainbow serpent, choking on salt and sliding elsewhere to seek freshwater. She takes us to Geraldton, where three Yamaji women perform an ‘unwelcome’ to country for Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party, and to the airspace above Wadjemup, where a ‘masterclass in amnesia’ means many tourists mistake it for a prettied-up holiday place, unaware of the spirits of the dead, unaware that they sleep on unmarked graves.

With these poems, Charmaine Green extends her hand to whitefellas, says: walk with me, let me show you another side to WA, let me share with you our colonial history, let me share with you the bearing of those past thieves on the present—the churches on ancient campsites, the racism, the wicked witches of the drug world ruining our beautiful, strong young people.

Kinsella takes the offered hand.

He tells us his grandmother ‘watched the blackfellas’ through hessian curtins, watched as they went beyond the town limits.

… out there was a truth she knew

was so close to home, if only

she understood how to see.

There’s a yearning in this—a yearning to understand. We find it again when Kinsella sketches the house of some whitefellas: there’s a carved emu egg, a boab and a Namitjira hanging alongside the footy pennants. Under the murk of the whitefella’s talk, something’s happening, something’s changing, an axis has shifted, attitudes are shifting.

They need to: Kinsella is unsparing and despairing in his depictions of racism. Some of the people in his poems are actively, viciously racist. We meet a group of vigilantes ready to shoot up a tin shack at the edge of town late at night. When Kinsella tries to stop them, they hunt him—he hides in the bush until daylight. We meet police in Geraldton that turn up the night of a fight. Kinsella’s wearing chips of blue metal in his scalp, his face is mush, he’s been beaten up by another whitefella. But the cops don’t want to hear that. They want to know which blackfella did it. The only blackfella at the scene, a Yamaji man, tried to break up the fight. Years later, the Yamaji man saw Kinsella said,

You’re a legend, bro – we –

we – know you didn’t tell the cops anything. I know you kept me out of it.

If you hadn’t, my whole family

would have paid and would still

be paying. In your name crimes

beyond imagining would

have been committed.

False Claims of Colonial Thieves offers a masterclass in remembering and a shout above the roar of the mining trucks. It turns a bright spotty on racism and holds the colonial thieves accountable. It’s a must read for Western Australians and for anyone who doubts the necessity of a truth telling commission. A fabulous collaboration by two important Western Australian poets, False Claims of Colonial Thieves was published by Magabala Books earlier this year and can be purchased at www.magabala.com or at any good bookshop.